Twister Story

Updated: January 3rd, 2016

Author: Reyn Guyer

As a young man working for my father’s design company, I knew our main job was to make in-store point of purchase (or POP) displays that drew attention to our Fortune 500 clients’ products. Our client list included Kraft Foods, Pillsbury, 3M, Brach Candies, S.C. Johnson and more. Our displays may have been clever (my father held over 120 patents in paper carton packaging design) but to me they weren’t the future. Whenever my entrepreneurial spirit pulled me in a new direction, my father reminded me of the primary rule at Reynolds Guyer Agency of Design: “POP displays pay the bills.”

Yet I felt boxed in. I even developed a fear of flying, as I headed off to Chicago, Cincinnati or St. Louis seeking to develop new clients. In time I put that assumed phobia aside when I discovered that I wasn’t anxious on planes at all if I was flying on vacation. One day, after returning from yet another edgy business trip, I went into my Dad’s office and confessed to him that if we didn’t start looking for a new path to take the business, I might have to look for another way to make a living. I shared my concern that our business model could never generate long term growth if we continued working order to order, with no possibility for residual income. To his credit, my father never discouraged me to try something new.

The year was 1965. I had acquired co-ownership of our Design Company. I was dreaming up a premium mail-in offer for a brand of shoe polish made by Johnson’s Wax. I thought, “What if consumers could mail-in a dollar and a box top from a shoe polish package, and in return, we sent them a game to play in their living rooms?” Since the promotion involved shoes, I envisioned a mat game that was played on the floor. The mat could have squares, like a giant game board, on which kids could step as they played. At that moment, I was suddenly aware that the concept held greater possibilities. As far as I knew, there were no games on the market where the players acted as the game pieces.

I went out into the area where we designed our in-store displays and pulled out a large sheet of cardboard and drew 24 one foot squares in a 4 X 6 arrangement. My first call for testers was in our offices and resulted in no lack of people wanting to play. Even our very pregnant receptionist was game. There were eight of us on the mat and I divided us into teams by color: green, red, blue and yellow. As I remember, I instructed each team to try to be the first ones to reach the diagonal square by moving to an adjacent square on their turn. It quickly became clear that the exact rules didn’t make any difference, because we were laughing so hard. The game was a riot, and I immediately knew this was more than a promotion for shoe polish. It had the makings of a retail product.

After playing that first rough prototype in our office, it was clear to me that when people were encouraged to be close together on a mat on the floor, they had fun. And it wasn’t just smiling fun. It was belly-busting-laugh-out-loud fun. So, I jumped into my next task which was to come up with a real game, played on a mat on the floor, that had winners and losers. I designed the mat as a 5 x 5 grid of squares. One team of two players wore red bands wrapped around their ankles and the other team of two wore blue bands. The first team to get their four bands of the same color in a row won the game. I called the game King’s Footsie. And then I took a prototype of the game to our client, 3M, a company known today for its office products, but which had a successful line of games in the 1960s. King’s Footsie really didn’t fit their more reserved brand of table-top games and so they passed on it. It became apparent that changing the course of our company would not be so easy. I needed a team.

One day, Chuck Foley, a salesman for a printing company we were doing business with was in our offices. He saw the prototype of the King’s Footsie game there and told me he had experience in the toy and game industry. It turned out that Chuck had worked for Lakeside Toys, and he had a friend, Neil Rabens, who was an artist and had worked for a children’s pool-toy company. (See We > Me: The Power of a Great Team). My Dad fully understood the possibilities of the “players are the game pieces” concept because he had witnessed the fun we were having. I sat down with him and outlined a new direction for our company, spear-headed by Foley, Rabens and me. Never one to tip-toe into anything, my Dad went to the bank and got us two years worth of funding. With his commitment, the Reynolds Guyer Agency of Design stepped boldly into the business of fun.

I hired Chuck and Neil and the three of us worked to take the “players are the game pieces” idea further. As a team, we seemed to synchronize well. We actually invented eight games that began by aiming at four year olds and progressed on up to word games for young adults. King’s Footsie was a stand out. But we were also making progress with having four colored circles spaced randomly on a four foot by six foot mat. When Chuck suggested that we line up each of the four colors in rows of six circles per row it definitely gave the game a more organized look. A few days later, Neil made the key suggestion that the players use their hands as well as their feet. Those two ideas and the premise that ‘people are the players’ on the mat were the keys to a subsequent patent. We added a spinner that required players to place their hands or feet on the colored circles and we dubbed that game Pretzel; “the game that ties you up in knots.”

Chuck and I then took the eight games we had developed to Milton Bradley, where we met with Mel Taft, the game giant’s Senior Vice President of Research & Development. Mel had never seen a line of mat games played on the floor. He liked them immediately and singled out Pretzel as a winner. Other executives at Milton Bradley were not so sure. They warned Mel that the idea of being that close to someone––especially someone of the opposite sex––was socially unacceptable. The rule we were breaking, almost broke the deal. Thankfully, Mel Taft was a rule breaker too.

“I was getting so much flack in-house that I took the thing home,” Mel recalled. “We had three other couples over and as soon as we started, I got to laughing so hard that I damn near had appendicitis. I knew this thing was worth its weight in gold … if adults could have that much fun…somehow we had to get it in the hands of consumers.”

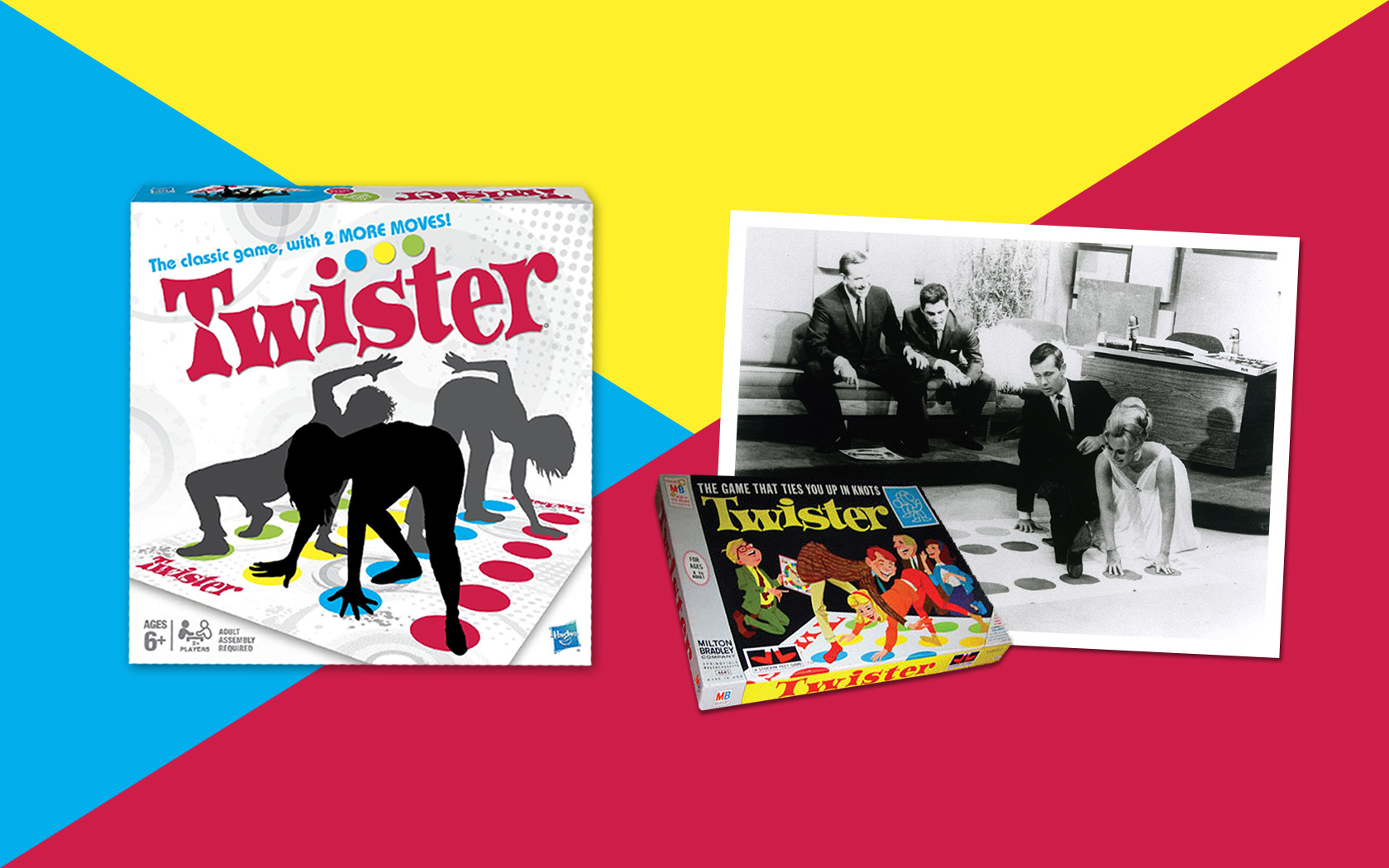

If the internal resistance Mel was facing weren’t enough, Milton Bradley’s lawyers found a toy dog named Pretzel, owned by a competitor, which meant that the name of the game had to change too. When Mel told me they had settled on “Twister,” I was not pleased. Having grown up in the midwest, where twisters killed people, I thought the new name was a terrible choice. But in the end, I learned that the name of a game is not really that important.

In 1966, Milton Bradley’s sales team showed the Twister game to some key retailers prior to the Toy Fair in New York, which is the toy industry’s major trade show. The buyers balked. I got a call from Mel. He told me that the game was “too risqué” according to the Sears buyer, and that he would not stock the game. Sears was so powerful back then, its decision on a product could make or break it. Twister was dead.

That’s what we and everyone in management of Milton-Bradley except Mel Taft thought. Little did we know that Mel, the ‘old-fox’, was aware that M B’s PR company had already been paid to promote the game. So, on May 3, 1966, with Mel in the audience, the PR company arranged to get Twister in the hands of Johnny Carson, star of The Tonight Show. It didn’t hurt that Johnny’s guest that night was the shapely actress and socialite, Eva Gabor. Watching the King of Late Night and Eva, in a low cut gown, on all fours on the Twister mat, sent America into hysterics and then, into stores the next day, asking for the game. What do you know? Sears reconsidered. Over three million sets were sold in 1967 and the rule-breaking game that “ties you up in knots,” hasn’t slowed down since.